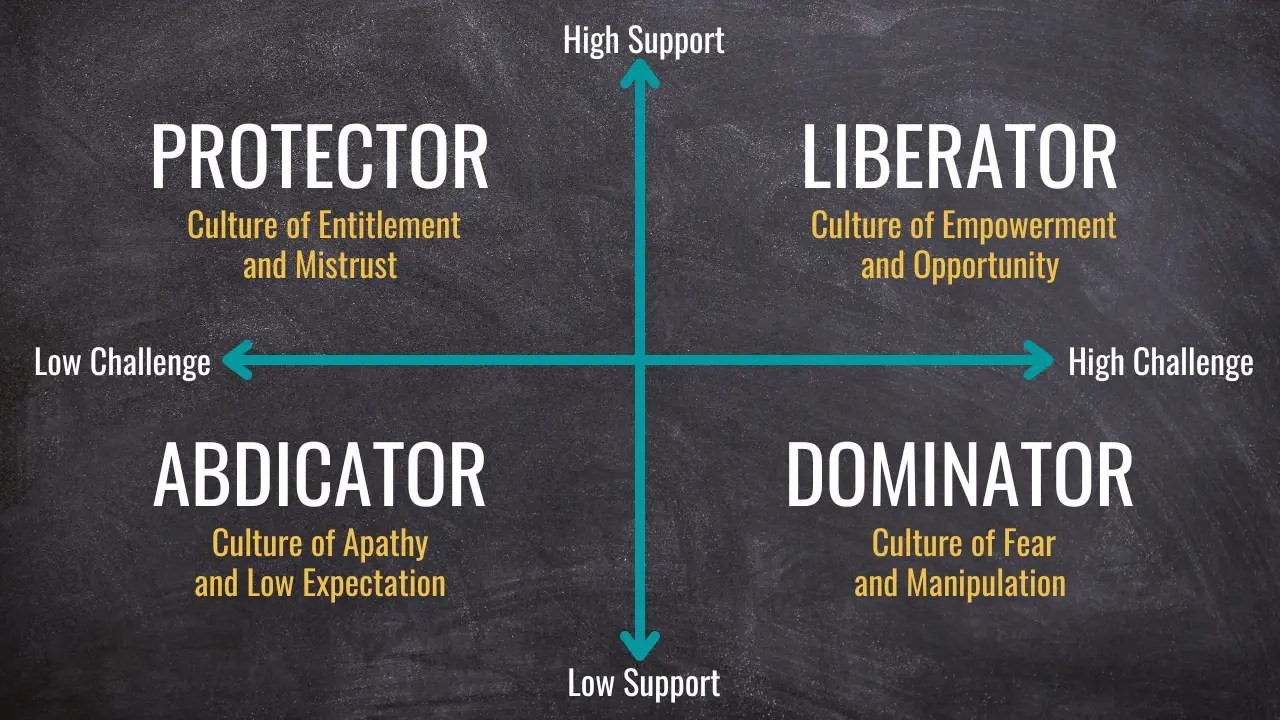

The above graphic (courtesy of Jonathan Sandling) and the linked article, explains why support is a key part of high challenge, if people are to change their practice and then improve. In the context of the “Sunday with Laura Kuenssberg” 23rd April ’23 interview with Amanda Speilman (England school’s Chief Inspector 2023), this article looks at the effects that emerge from what is inspected and how.

1. Summary of what is inspected:

Ofsted inspects to the Government’s requirements. This focuses school attention on results, top-down education policy and politicians’ notion of what matters. We argue that the focus should be on teaching and learning, the needs of individual classrooms in their context and on what the pupils are good at. This will optimise learning and make education a better and a healthier fit for the pupils coming through the system, rather than make pupils fit into other’s views of what is best for them. The latter forces compliance over competence, and reduces creativity.

Amanda Spielman made a point that they are inspecting in the only way possible to meet the Government’s specific requirements. She is probably right, and no one will sensibly argue for static or reducing standards; however, what is being inspected now can still cause problems.

Different classes in different schools in different areas with different needs are being measured against one-size-fits-all criteria. We know from the most recent research into the early development of children that specified and high academic standards are not the only possible or best outcomes from all pupils in all schools. There will be schools that will struggle to satisfy all criteria adequately while still providing a very good service to its pupils; yet in the current system, may spend considerable time with a poor judgement, not necessarily through any specific fault of their own. The process of preparation for inspection tends to exacerbate this problem, like this:

What school leaders tend to focus on:

• Results of the outcome of SATs and GCSEs for example;

• Top-down pedagogy and curriculum, appearing less relevant to some older pupils;

• The school’s own performance with regard to compliance – how intelligent is the child?

What school leaders could focus on:

• Improvement of teaching to achieve better learning. This gets results in the best way;

• Bottom-up learning that actually engages classes, based on pupils’ emergent needs.

• What the individual pupils need – how is the child intelligent?

The economy requires educated, passionate and creative people to set up and run new enterprises successfully (1). In the way described above, UK education tends to stifle creativity, making schools less healthy mentally (2) and the people who pass through it ultimately less productive (3). This is the wider problem, not literacy and numeracy. Poor literacy and numeracy could be caused more by a lack of purpose felt by people who pass through many state-maintained schools under current conditions.

2. Summary of how schools are inspected:

The process of inspection is neither the best way to help schools improve, nor does this type of quality assurance form a substantial part of any other professional development or process of improvement in industry or business. Support, understanding and time to improve does, and the people with the expertise to help are the inspectors. The current process will tend to disable the best improvement of poor schools, which in turn accelerates academisation and therefore privatisation of education (in the UK).

In industry and business, the process to assure regulatory compliance starts with support, developing understanding and then realistic remedial action plans, and providing reasonable time to put actions in place. This is true of regulatory agencies such as the Environment Agency, Health and Safety Executive and all (BS/ISO based) quality assurance bodies. It is only when continuous improvement is not happening fast enough or at all, or in cases of significant breaches of legal compliance, do they consider applying potentially negative or punitive consequences or sanctions. Why then, particularly within social sector organisations, does Ofsted apply the consequence of immediate and potentially destructive down-grading (4), largely without (or at very least before the possibility of) offering the support, understanding and time to improve (5)? As Mrs Spielman said, her inspectors have the expertise and have been in the position of being inspected. Why can we not utilise this expertise during and after the point of inspection to develop and implement improvement plans? Particularly when similar and potentially more serious occurrences in industry have the time and expertise?

Additionally, why do Ofsted not also hold a mirror up to policy makers, as inspectors must be able to see and understand the effects of policy in schools – in a way that government cannot?

In education, we as adults are required to model the best / optimal behaviours for learning (6). Then, why do we treat school professionals in ways we would never consider appropriate for children, let alone businesses or any other professionals (7)? How is this good for recruitment into teaching, particularly in the current climate (8)? Amanda Spielman (and any Chief Inspector) may be bound by law to following instructions, but from this interview, she appears to not be taking any account of modern research around the best approaches to organisational improvement (9), nor does she yet appear to be paying attention to the life-changing consequences of a small number of the inspections she is responsible for (10).

Conclusion:

What is being inspected, governed by the UK framework, only requires compliance and provides a crude measure of that compliance. The items missing from the inspection process – that are present in many other professions – are the support of schools to improve, and representation of schools to policy makers: if these were in place, few schools or teachers would have any issue with inspections.

Without these in place, inspections are merely compliance-policing of policy, by people – many of whom have no recent or current experience in education.

Notes:

① No one can know what jobs will be needed in an ever-changing economy over time. Companies not only adapt to the market but also to the capabilities of the staff they can recruit.

② Ideal Mental health could include attributes such as positive self-attitude, self-actualisation, resistance to stress, personal autonomy, accurate perception of reality, adaption to environment.

③ It is well documented that we have been and remain less productive than any other European country we may want to be compared with, over the last 50 years or more.

④ The grading by Ofsted is a problem – actually any grade has a consequence: a high grade suggests less or no further improvement is necessary, and a low grades position people in the organisation as less competent and less able to improve – just at the time when confidence and energy for improvement is needed most. Public shaming during this time for a school cannot be the best way or the best time to get the best out of school staff, who need to be at their most confident at that time.

⑤ The support systems in schools are not adequate, if increasingly more documented consequences of inspections are to be accepted. High challenge can only be healthy if high level of support is also provided: without support, high challenge creates unproductive stress. Prevention is better than cure. Modern research into learning at any level suggests that the best (optimal) learning occurs when the individual feels they are in an environment of high challenge and high support. This applies to children and is the basis for good teaching and learning in classrooms. It also applies to professionals, who need to continue to learn – throughout life – in the best way possible: an adult who feels under threat (personally or their career) is going to make poorer decisions than in the same situation with lower direct consequences, when – just at the time when stability and collaboration is needed to facilitate the best and fastest learning is needed. Consequence of a poor grading: typically, pupil and teacher applications to join schools reduce, some pupils and teachers may leave, judgement applies just at the point when the school needs

⑥ Growth mindset believes that learning from failure is the most powerful form of learning. Learning is at its most powerful when the mind experiences a perturbation to our current thinking. It does not come from the threat or application of high stakes and serious consequences, that simply position professionals – and particularly pupils – as incompetent.

⑦ Definition of a professional: Someone who is concerned with life-long learning, both formal and informal learning opportunities, situated in practice. They can be intensive and collaborative and incorporating evaluation. Approaches include consultation, coaching, communities of practice, lesson study, mentoring, reflective supervision and technical support.

⑧ The recruitment and retention crisis are problems currently: along with the imminent closure of potentially 61 out of 240 Initial Teacher Training providers (by failure to gain re-accreditation), fewer trainees are joining and remaining in the profession.

⑨ Cook, S. D. N., and Brown, J. S. (1999).

Bridging Epistemologies: The Generative Dance between Organisational

Knowledge and organisational Knowing, in Organization Science Vol 10, No 4

(July – August 1999, pp381 – 400.

California: J – Stor ( http://jstor.org/journals/informs.html )

Also: Collins, J. (2001). Good to Great: Why some companies make the

leap . . . and others don’t. London; The Random House

Group.

⑩ https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-berkshire-66167021