Whether one advocates a cultural or a computational view, it cannot be denied that computationalism has penetrated culturalism in important ways. The enormous profusion of technology among the public, and AI and robotics over the last 100 years and with it the increasing knowledge of computing has in itself affected our behaviours in many tacit and implicit ways. Organisations nowadays increasingly define and construct policy documents outlining in minute detail contingencies and procedures to follow which take on an appearance not so dissimilar to computational processes. Many such policies have to show coherence with legal or statutory guidelines which in their own way serve as operating systems within which policy needs to comply. Risk assessments, multiple choice testing, criteria matrices, league tables and so on increasingly involve numerical calculations intended to aid, though sometimes they substitute and interfere with, careful human judgement. We still reference the ‘computer says no’ line nowadays, nearly 20 years since it was first aired, and the increasing access to communications technology which allow individuals outlets to share their feelings has led to the propensity for ideas to spread and ‘go viral’ in ways that were inconceivable before 2000.

There is no denying that algorithms increasingly influence, some might even say govern, our lives. The extent to which algorithms determine the content we are exposed to through social media platforms and in so doing influence our political, consumer, and social choices is deeply pernicious. They are so because they directly prey on human vulnerability (e.g. the need for social acceptance, the desire to attain absurdly high standards of beauty etc). Once the algorithm ‘learns’ our predilections we soon face a bombardment of ever more content related to one’s search history, interests, and tastes and generates the irresistible itch of device addiction. This ‘rabbit-holing’ phenomenon, in which users are led down a road to content that is ever more tempting and irresistible to access has enabled the widespread proliferation of fake information and driven wedges of division between communities. It has also compounded wider social concerns about mental health, feelings of disenfranchisement, isolation, anger, division and polarisation. The power and efficacy of this process is presenting those with unethical intentions with great opportunities to achieve their goals. As educators this profoundly re-energises our mission and need to uphold the ethical safeguards to both protect and inform those in our society from these threats.

Culturalism would recognise a danger, though, in thinking that the current challenges constitute a complete break from the past. As we have seen from the tenets of culturalism’s focus on historic meaning, it is possible to see many of the challenges spawned from technological invention are very much situated in the past and encountered before. The ‘big tech’ companies may be following, as it is termed by insiders within them, a model of ‘surveillance capitalism’ that is bringing about profits and yields never seen before but it is still capitalism fuelled by industrial technology. HG Wells’ (1920, p. 594) prophetic quotation that ‘human history becomes more and more a race between education and catastrophe’ seems particularly fitting a hundred years later. He went on to say ruefully contemplating the aftermath of World War One; ‘against the unifying influence of the mechanical revolution, catastrophe won.’

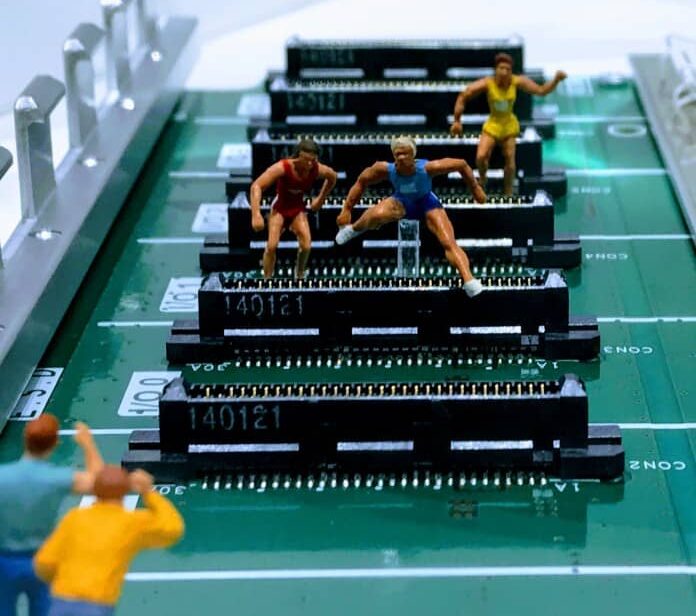

One of the most notorious examples of computationalism at work and the mechanical revolution of which Wells speaks was in the giant River Rouge Ford Factory in Detroit which was manufacturing the Model T during the 1920s. Building a car is of course a highly skilled process and it would require skilled artisans several weeks to assemble one on a garage floor in the 1920s. Ford, however, studied the process of car building and assembly closely and successfully broke it down into hundreds of smaller unskilled jobs. In a manner of speaking he reduced the process of building a car to a form of programming code which he would make humans, rather than machines learn. Furthermore, rather than hiring skilled artisans, he then brought in low-skilled immigrant labour (in their hundreds) and taught each individual to do one of those simple jobs. He had created an assembly line in the process with each immigrant worker repeatedly doing their simple task (e.g. connecting the drive-shaft, riveting the chassis, mounting the wheels etc etc) as the car travelled from one end of the factory to another increasingly taking a recognisable form. By the mid-1920s, the factory was producing a car every 10 seconds! This is an example of how knowledge can be re-processed explicitly into a system of simple steps, which just needed to be learned quickly and simply, each one building more onto the preceding one until at the end of the process there was a moving, functional car. They may have been all exactly the same cars, and not particularly special, but they moved and did the job. Can anyone spot the parallels between a set-up like this at the Ford plant, and schools?

So how would a culturalist understand the River Rouge plant and its computational basis? By acknowledging that the culture of such an institution was ear-marked by compliance and control. Although it is not inevitable that workers in cultures like these divest themselves from it, it is not surprising that many did especially as this kind of employment culture was so new to them. We should also remember that the myth of American freedom was in many cases what drew them to resettle too and many immigrants may have felt a jarring coexistence between what was promised and where they ended up. Why would we think that repeated tasks on an assembly line would generate in itself much meaning for the workers, though obviously the incentive of a job and a living would have led to many of them doing it? It is interesting that very few of Ford’s mechanical labourers, by the time they had served years on the assembly line had learnt how to build a car on their own, from scratch. Although they would have had an understanding of the principles involved and some of the practical considerations, many were not able to actually build a car if they were left on their own and given all the materials and tools for doing so. This was because the assembly line workers were not let into the design and specification practices of the models they were building and without the necessary scaffolded infrastructure of machinery facilitating the process of construction, it was not a feasible proposition for an individual worker to even try to construct a car on their own. The work and the process would not turn them into artisan engineers and the workers could see that it would not. With clear and visible limits to the available trajectories for the workers to develop and learn within the car industry, it is not surprising that many began to create alternative practices for themselves. Some of these were in defiance of the rigid systems of compliance, for example the unionisation and organisation of workers into labor unions. Ford’s treatment of this activity is well noted.

There is more to this, however, than just the age-old battles between management and worker. Culturalists would also look for what the workers did to bring meaning into their lives; for example how many of the assembly line workers began to practise their English skills with each other (many were from a wide array of different countries and could not communicate in their mother tongue with each other) to communicate, associate and make relationships with each other while they were doing their dull and repetitive jobs. Not only did this help them to overcome the boredom of the work but it helped them to assimilate into the host nation too. Interestingly, this did not create conflict with Ford or the management hierarchies of the organisation. Instead Ford actively encouraged the workers to develop their English skills further and arranged for classes to be put on for his workers. In this way, Ford actively encouraged the ‘Americanisation’ of his workforce. The promise of English tuition, as well as a wage hike, attracted many workers, and as we shall see in another post, the significance of what is learned from these ‘wandering minds’ did not stop there. Those same factories and factory workers were to create a whole new genre of popular emblematic ‘motown’ music to the rhythms and drones of the factory process (Temple, 2010). Life is full of examples like this –and it is a reminder that teachers must pay attention to what is emergent in their classrooms and pupils; what this tells us about the pupils and their interests as well as what it tells us about the systems that are being imposed. An interesting article by Solomon et al. (2006) studies the activity of people at work in organisations and what they do in between their actual job that helps to bring more meaning to their lives.

When it comes to learning to teach, there is now a huge proliferation of documents, policies, research, guidelines as well as claims that teachers have to discern and judge for themselves. It is possible that some schools tacitly do not accept certain kinds of teaching and this can confine teachers’ training and breadth of experience. In a similar way, it is possible that in relation to pupils certain schools do not accept or recognise certain kinds of learning either. For teachers this is a danger because getting good at teaching must involve more than simply acculturation to a school or simply getting good at knowing the school. Other schools are not the same (think about the Ford workers who after years of making cars did not actually know how to make cars!).

Culturalism and computationalism may seem incompatible with each other but they are not. For one thing, the computational view is pervading and indeed changing our cultures and its tendency for rigid, occasionally mindless rule-bound bureaucracies are everywhere to be seen. We are affected by the rules they produce and not always badly either. In fact quite often they are useful interventions for fighting unpleasant phenomena that have grown in our cultures – e.g. equality law to fight discrimination or traffic rules to establish order on the roads. So we must not think that all culturalism is good and all computationalism is bad. A teacher needs to be aware of the dangers of each i.e. meaninglessness, boredom, cold impersonality and abstraction that tends to pervade computationalism and the meaningfulness that could have unpleasant or personal implications, emerging practices that are distracting or irrelevant (to the teacher) that are the occupational hazards of culturalism.

In teaching there needs to be a careful recognition that there are limits to what can be achieved by strict and rigid application of rules. If subject areas and disciplines could be completely reduced to a series of rules, it is tempting to think that they would be easier to teach and learn. This is, however, unproven and highly questionable. As we have seen, when complex and fascinating processes are reduced into a series of rules that are repetitively followed and routinely adhered to, fascination and interest in them becomes short-lived. How often, after all, do teachers have to compete with pupils for attention and when does emergent activity that is more interesting to pupils but irrelevant to the subject being taught become the norm? Subject areas and disciplines of course do have rules but a rigid and brittle adherence to them can limit achievement just as much as riding roughshod over them. And when pupils’ interest and attention wanes, it is tempting for teachers to invoke an even stricter and rigid application of institutional rules of discipline – the very thing feted to perpetuate the problem and drive emergent activity ‘underground’.

Why wouldn’t people be interested in the miraculous properties of chemicals, or maths or the cosmos, history, geography, art, design, and so on? Find out what it is about the questions that fascinated the people whose shoulders we now stand on! It will always come down to the same – they found meaning and purpose in what they did. So teachers must observe pupils closely and develop a knack for sensing whether the material is making sense or not. Are the pupils going through the motions or are they thoroughly engaged and grappling with difficult problems – and consider in the former case what can be done to make things more meaningful; and in the latter what can be done to capture their activity into notes, formulae or rules of thumb that can make a tangible record of the work they have done.

Part 3:

See below for posted comments. Do you have something to add?

Bredo, E. (1999). Reconstructing Educational Psychology. In P. Murphy (Ed.), Learners, Learning and Assessment (pp. 23-45). London: Sage.

Brown, J. (2000, March/April). Growing Up Digital; How the Web Changes Work, Educationa nd the Ways people Learn. Change, 11-20.

Bruner, J. (1997). The Culture of Education. Boston: Harvard.

Casey, G., & Moran, A. (2012). The Computational Metaphor and Cognitive Psychology. Irish Journal of Psychology, 10(2), 143-161. doi:10.1080/03033910.1989.10557739

Cook, S., & Brown, J. (1999). Bridging Epistemologies: the Generative Dance Between Organizational Knowledge and Organisational Knowing. Organization science, 10(4), 381-400.

Hammersley, M. (Ed.). (1993; rpt. 2003). Educational Research: Current Issues. London: Paul Chapman/OU.

Hammersley, M. (2006). What’s Wrong with Ethnography? New york: Routledge.

Hirsch, E. D. (2016). Why Knowledge Matters: Rescuing our children from failed educational theories. Boston: Harvard.

Kirschner, P., Sweller, J., & Clarke, R. (2006). Why Minimal Guidance during Instruction does not Work: An analysis of the failure of constructivist, discovery, problem-based, expereintial, and inquiry-based teaching. Educational Psychologist, 41(2), 75-86. doi:10.1207/s15326985ep4102_1

Moore, A. (2015). Knowledge, Curriculum and Learning: ‘What did you learn in school?’. In D. Scott, & E. Hargreaves, The SAGE Handbook of Learning (pp. 144-155). London: Sage.

Ofsted. (2019). The Education Inspection Framework. Manchester: Ofsted.

Parker, J. (2002). A New Disciplinarity: Communities of Knowledge, Learning and Practice. Teaching in Higher Education, 7(4), 373-386.

Ryle, G. (1949). The Concept of Mind. Harmondsworth: Peregrine.

Sfard, A. (1998). On Two metaphors of Learning and the Dangers of Choosing Just One. American Educational Research Association, 27(2), 4-13.

Solomon, N., Boud, D., & Rooney, D. (2006). The In-between: Exposing the Everyday Learning at Work. International Journal of Lifelong Education, 25(1), 3-15.

Sternberg, J. (2003). What is an ‘Expert Student’? Educational Researcher, 32(8), 5-9.

Temple, J. (Director). (2010). Requiem for Detroit? [Motion Picture].

Wenger, E. (1998). Communities of Practice: Learning, Meaning and Identity. Cambridge: Cambridge.

Young, M., & Lambert, D. (2014). Knowledge and the Future School: Curriculum and Social Justice. London: Bloomsbury.