I have been working recently (or at least before the Covid situation arose a year ago) with a number of schools bringing historical objects into classrooms for pupils to touch and handle. This initiative has been part of a project involving academic historians very interested in the ‘material turn’ in historical studies, which puts the study of objects at the forefront of research. The objects we brought into schools were from Chester’s Grosvenor Museum which has a vast collection of unstudied Medieval material found in and around the city of Chester over the last century. There was nothing particularly unique about the objects as they were every-day personal possessions, for example belt buckles, keys, shoes, pilgrimage and devotional tokens and so on. Yet the fact that they have survived since the medieval era clearly makes them remarkable and of great interest. The children who handled them were fascinated and it was genuinely wonderful to see their eyes open wide at the feel of these objects.

There are however a multitude of historical and pedagogical problems in studying these objects especially when there is no known narrative behind them. We know nothing of the people who owned them, very little of the specific locality where they were found, and very little of the journey these objects made to get to a museum collection. So to what extent could a historian make any claim to knowledge from these objects? I raise the point to emphasise how this problem has led to innovations in thinking about historical methodology, and while these may be uncomfortable and on occasion controversial, especially regarding the relationship between evidence and knowledge, these innovations do nevertheless raise important questions for teaching, education and the construction, storage, retrieval and understanding of knowledge.

One of these questions was pointed out by Dr Katherine Wilson of the University of Chester, a Senior Lecturer in Medieval History, who is one of the pioneers of this project (please see The Mobility of Objects Across Boundaries 1000-1700 (MOB) | an AHRC network (wordpress.com)). As we observed the pupils handle and feel the objects and discuss, explore, accept and reject ideas and speculations, Katherine raised the following question: isn’t it true that we often conceive of old objects as static and inert, somehow carrying the vestiges of outdated and obsolete ideas and mentalities that led to their creation and manufacture? Shouldn’t we conceive these objects by contrast as being dynamic entities that have travelled through several people’s lives on their obscure journey to a classroom?

A further fascinating observation that she made was in relation to the way the pupils interacted with the objects. We normally think of people doing things with objects but we very rarely ever consider that objects do things to people as well. If our relationship to objects is genuinely interactive then we should consider the agency of the object as well as its user.

This brought out a multitude of questions for me in relation to the handling of objects and the ‘nature of things’ because these objects will certainly have done things to people: the shoes enabled people to travel; the keys opened doors or chests for people to store or hide things; the pilgrimage badges changed people’s status. If we are to conceive of the objects as dynamic entities whose purpose and use has changed over time then we should also acknowledge people’s endless inventiveness and their propensity to use objects in ways that they were not originally intended to be used. Was the medieval shoe used to beat people or children I wonder? Was the key ever used for stirring or mixing cooking? Were the pilgrimage badges ever counterfeited? Were the decorated tiles ever used as door-stops? These questions show the affordances that these objects potentially offered to people in the past and show that the objects are anything but static in their use and purpose.

As this question began to settle in my mind I began to reflect on other instances of this in relation to other, bigger questions. For example, what does this mean about potentially problematic historical objects like slave manacles, or weapons used to inflict pain or death? I remember a handling session at the International Museum of Slavery in Liverpool, in which slave manacles used in the transatlantic slave trade were handled by children without a genuine understanding of what they did to people in the past. The children had an understanding of this form of slavery but this was often a rather simplistic and stereotyped understanding involving the infliction of brutality and pain, but without a serious consideration of the economic status of black slaves as chattels, the ownership of them, the buying and selling, and the ‘breaking’ of people as an important element of enslavement itself. If one’s understanding of slavery were more profound, what would touching an implement like a slave manacle mean and involve? The key issue here is that the object is not just a representation of enslavement, it does not just reflect the abstract concept of ‘slavery’, it is an object which actually enslaved people. This is a sobering thought and one which may make us think more deeply about making such objects available for children to handle in order to more fully appreciate their historical meaning.

I am reminded of the famous film 2001: A Space Odyssey, in which the bones of a dead animal enable a group of prehistoric apes, soon to evolve into humans, to discover weapons and tools, which in turn enable them to take over the domain held by another group of apes. Through one of the most famous cuts in movie history, the story moves from the first human invention to the culmination of human invention in the form of space-age travel many millennia afterwards and the HAL9000 computer revealed to be installed on one of the spaceships. This is the notorious computer which, as itself an object only simulating human characteristics, does horrible things to the human beings in the crew.

There is a critical difference between agency and responsibility. If we ascribe agency to objects in the way that they would give individuals ideas, afford behaviours and opportunities, responsibility for those choices remains of course with the human actors who use them. It still required humans to actually shackle the slave manacles on to their slaves. HAL9000 killed a crew-member on board the ship in 2001: A Space Odyssey but humans programmed it with the coding algorithms that made it necessary: ‘nothing must be allowed to jeopardise the mission’ and ‘the HAL9000 computer functionality is essential to the mission.’ Like all computational devices no matter how sophisticated, HAL9000 is forced to comply with its own coding algorithms predetermining its choices and actions. Unlike human beings, it cannot suspend them. A mark of expertise in humans is not just a mastery of the rules governing their endeavours but the knowledge of when it is necessary to suspend, rethink, or repurpose those rules. This simple fact will always evade coders, for there will always be a space within human endeavours that is beyond specification, where the dark matter of social science, the tacit, implicit, intuitive and invisible lurk. (see related posts on differences between computationalism and culturalism).

When we took the medieval objects into schools I was struck by the attention and engagement they stimulated in pupils, even those who disliked history as a subject. At once there was a ubiquitous fascination the like of which is rare in school classrooms. For a more detailed account of the classes we took them into please see Touching, feeling, smelling, and sensing history through objects / Historical Association.

The objects were genuinely doing things to the pupils in that they were awakening the pupils’ historical curiosity and imaginative sense of the past. Though the objects could yield very little information of their actual history (for example how they ended up where they were found; where they were kept originally; who their owners had been) it did not seem to put the children off or prevent them engaging in the negotiation of meaning. The pupils may well have been, therefore, confined to speculation and hypothesis and a sense that there were multiple possible answers yet this did not detract from their engagement. This was especially interesting given that history learners commonly do have difficulty with the notion that history has to be constructed through evidence, educated guesswork, speculation and story-telling. This is well summed up in Peter Lee’s (2005, p. 62) work by a Year 6 pupil, Annabelle, who replied with the following comment when asked to reflect on the problem that there were always multiple accounts of the same story:

Something in history can only happen one way. I got up this morning. I wouldn’t be right if I wrote I slept in. Things only happen one way and nobody can change that.

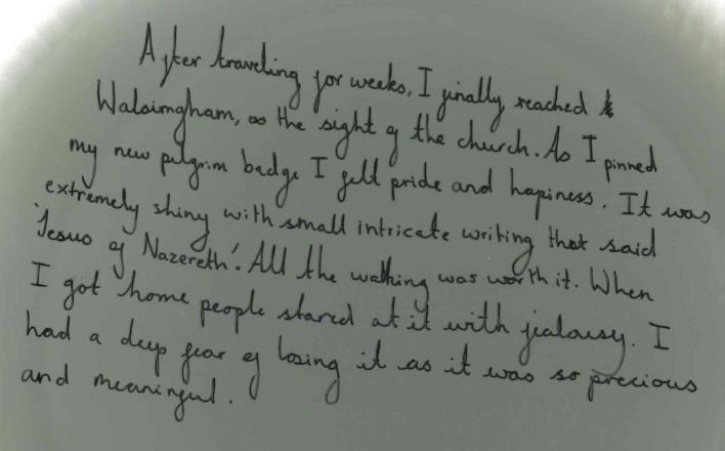

The problem with this kind of conception of history is that it makes the processes of hypothesis and speculation pointless – or at best mere indulgent recreation. One could imagine Annabelle or anybody sharing her view, would lose motivation in any such activities. Yet this did not happen with the objects. Look at the examples of pupils’ work in which the pupils chose one of the objects and placed it into an imagined vignette of someone’s every-day life in the Medieval period. One cannot claim these to be true but they are special in a different sense. They represent connection between the children and their imagined counterparts of many centuries before living in a plausible construction of their every-day experience. If objects can make this kind of historical thinking available to pupils, is there an opportunity to seriously challenge simplistic assumptions about the past, approaches to source-work, and stubborn notions of history as a received subject?

Certainly this is one of many considerations we will be giving to this project when we can once again take objects into schools – hopefully quite soon.

To read more about this see:

Appadurai, A. (Ed.). (1986). The Social Life of Things: Commodoties in cultural perspective. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Bird, M., Wilson, K., Egan-Simon, D., Jackson, A., & Kirkup, R. (2020). Touching, Feeling, Smelling, and Sensing History through Objects: New opportuntities from the ‘material turn’. Teaching History(181), 40-48.

Downes, S., Holloway, S., & Randles, S. (Eds.). (2018). Feeling Things: Objects and emotions through history. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Howell, M. (2010). Commerce Before Capitalism in Europe, 1300-1600. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Johansson, P. (2019). Historical Enquiry with Archaeological Artefacts in Primary School. Nordidactica – Journal of Humanities and Social Science Education(1), 78-104.

Jurkowlaniec, G., Matyjaszkiewicz, & Samecka, Z. (2018). The Agency of Things in Medieval and Early modern Art: Material power and manipulation. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Lee, P. (2005). Putting Principles into Practice: Understanding History. In M. Donovan, & J. Bransford (Eds.), How Students Learn history, Mathematics and Science in the Classroom (pp. 29-78). Washington DC: National Academies Press.

Rublack, U. (2013). Matter in the Material Renaissance. Past and Present, 219(1), 41-85.

Trapani, B. (2019). Who Can Tell us Most about the Silk Road: historical scholarship, archaeology and evidence in Year 7. Teaching History(177), 58-67.

Vella, Y. (2010). Extending Primary Chldren’s Thinking through Artefacts. Primary History(54), 14-17.